Hurricane Season is long. June through November is half the year. But it’s in October when Hurricane Season starts to gnaw at our last nerve.

We’ve talked about them ad nauseam for the first three or four months of the season, then just when we think we’ve escaped another bad season, we get a last-minute drumming by Mother Nature. Hurricane Season can be cruel like that.

I write a lot about what lies ahead in this newsletter. The daily updates walk us through the life cycle of the season together – from the messy homegrown systems in June to the wave-watching that starts in July to Cabo Verde Season that stretches into September to the blockbuster hurricanes of October.

If you’re reading this, you know how stress-inducing the ebbs and flows of the season can be.

We could all use a palate cleanser right about now, so let’s talk about a more savory topic: when storm landfalls start to wind down.

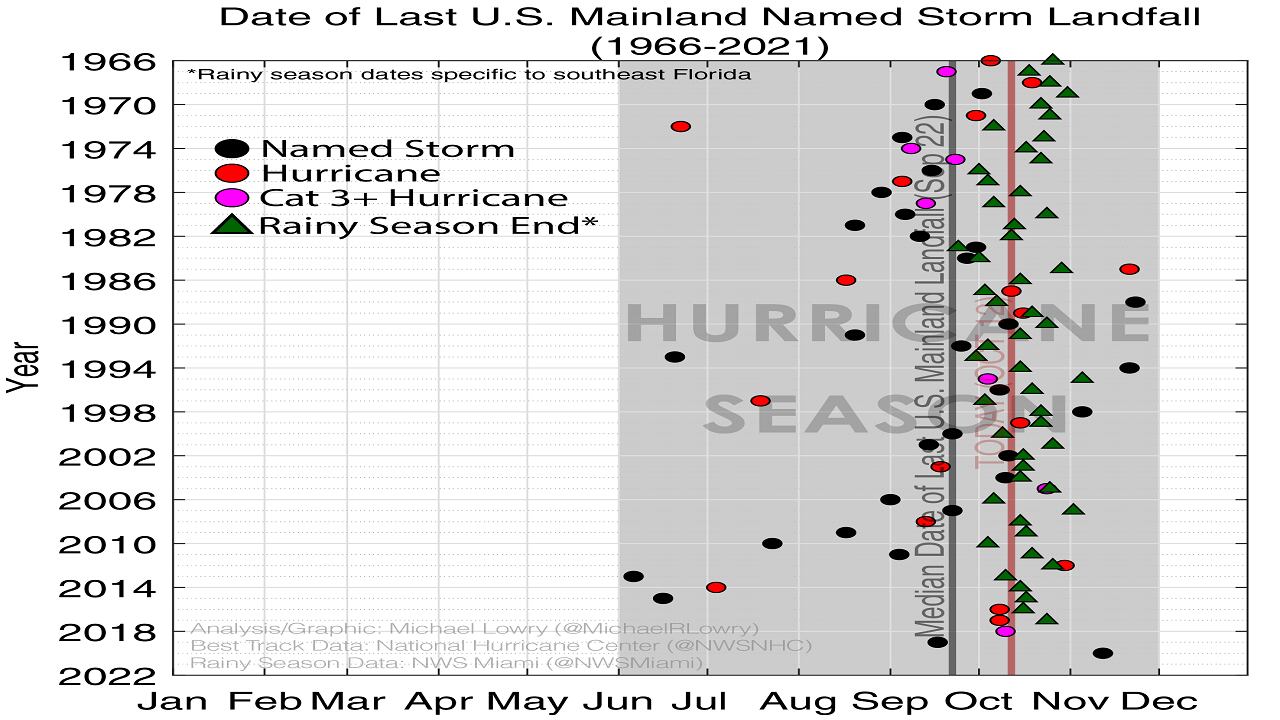

Analyzing the last 56 years of reliable records (since the advent of weather satellites in the 1960s), at first glance, there doesn’t appear to be much of a pattern to when landfalls (named storms only) taper off here in the mainland U.S. In some years like 2015, we see a strike in June and that’s it.

In other years like 2020, we’re pushing mid-November with the landfalls. Overall activity certainly has an impact, but to some degree, it’s a matter of luck (or lack thereof) from steering patterns.

A closer look at the data, however, does reveal some key takeaways. By mid-October, in most hurricane seasons – about 8 in 10 – the U.S. mainland has already observed its last landfall.

It by no means guarantees the U.S. Gulf and East Coasts are off the hook after mid-October, but there’s a noticeable decline in the threat for landfalls after mid-October compared to the beginning of October.

What might be the reason?

By mid-October, cold fronts from the north start to make it deep into the Gulf of Mexico and off the U.S. East Coast. In fact, we have one poised to deliver a shot of fall air through South Florida by this weekend.

When cold fronts begin to routinely make it into the Florida Keys, they do two things. First, and most importantly, they sharply increase storm-busting wind shear off the coasts of our hurricane states and secondly, they begin to cool down the warm water fueling storm activity. The combination is hurricane kryptonite.

What’s more, we can loosely tie the landfall winddown back to a unique aspect of South Florida’s climate – the end of rainy season. For non-natives or recent transplants, South Florida has two primary seasons – rainy season and dry season (or summer and winter).

Rainy season is characterized by warm, humid days with frequent thunderstorms while dry season is characterized by what I like to call meteorological Shangri-La. Dry season is what we taunt our northern friends with all winter long.

Prior to 2018, meteorologists assigned varying dates to the end of rainy season based on several factors, but the National Weather Service now uses the set calendar date of October 15th to mark the official end of rainy season. It’s no coincidence that this also falls around the time mainland U.S. landfalls taper off.

Examining past rainy season end dates from NWS Miami, the last U.S. mainland landfall happened by or before the end of South Florida’s rainy season in 9 of 10 hurricane seasons over a 62-year period.

That’s a pretty good track record. Grand finale hurricanes like Wilma in 2005 can also help launch us into dry season.

A 2017 study on the rainy season in Florida found in about half the 58 years examined, tropical cyclones were in the vicinity of the Florida peninsula near the time rainy season ended, leading the authors to conclude the drying out may be accelerated or activated by late-season storms near Florida.

While it’s premature to declare hurricane season over for South Florida, the sweeping passage of our first big cold front and the official end of rainy season this weekend does offer some reassurance that the worst may be behind us.

November storms, when they happen, tend to prefer a Florida track (see Gordon in 1994 or Keith in 1988) because tropical systems like to ride along those cold fronts and towards Florida, so hold onto those supplies until Thanksgiving just in case the tropics find a second wind.

In the meantime, rest assured newly minted Tropical Storm Karl in the southern Gulf won’t be a threat to South Florida as we enjoy the protection of those storm-busting upper-level winds along with a subtle taste of the dry season to come.

Copyright 2022 by WPLG Local10.com - All rights reserved.